Competitive analysis frameworks are indispensable for anyone who wants to extract meaning from intel and inspire action across their organization.

When we talk about competitive intelligence, we’re talking about a three-step process: track, analyze, act. Track, of course, refers to the collection of data: Competitor X launched a new product, Competitor Y parted ways with their sales leader, etc. The task of gathering intel is a time-consuming one—unless you use Crayon, that is—and it’s only becoming more time-consuming as industry competition intensifies and corporate digital footprints expand.

In order to get a return on the time you spend gathering intel, you need to determine the meaning—the key takeaway—behind each datapoint. Competitor X launched a new product. So what? Competitor Y parted ways with their sales leader. So what?

It’s only when you’ve established the so what that you’re ready to get a piece of intel into the hands of the appropriate stakeholder(s). And it’s only through competitive analysis frameworks that you can establish the so what on a regular basis.

What are competitive analysis frameworks?

Competitive analysis frameworks are structures (or models) that make it easier to organize, connect, and interpret competitive datapoints.

Imagine a whiteboard. Every time you come across a piece of competitive intel, you have to record it on the whiteboard. You’re not allowed to devise any kind of organizational system for the data you’re collecting; all you can do is write in simple rows and columns. After a while, you run out of space—you’ve recorded dozens of datapoints.

If you were to take a step back, look at the whiteboard, and scan through the fruits of your competitive research, do you think you’d be able to pull out the key takeaways? Perhaps—but it would be a challenge. Without any kind of structure, you’d likely struggle to see the meaning behind the intel.

This is why we have competitive analysis frameworks: to help ourselves turn intel into insight.

3 time-tested competitive analysis frameworks

By this point, you’ve probably noticed that we’re speaking in plurals; there’s more than one competitive analysis framework that you can use to your advantage. And, no—there are no good or bad options. Different frameworks will be more or less useful depending on the intel you’ve gathered and the goals towards which you’re working.

1. Comparisons

How do you stack up against your competitors from a product features perspective? From a market positioning perspective? From a pricing perspective? Comparison frameworks enable you to answer these questions—and myriad others like them.

A comparison framework is a structure that allows you to directly compare your company to its competitors against one or more variables. The variables you select for your analysis depend on your goals and the kinds of intel you’ve collected. (For clarity, you should establish goals before gathering intel. Different goals require different kinds of intel, and different kinds of intel lend themselves to different competitive analysis frameworks.)

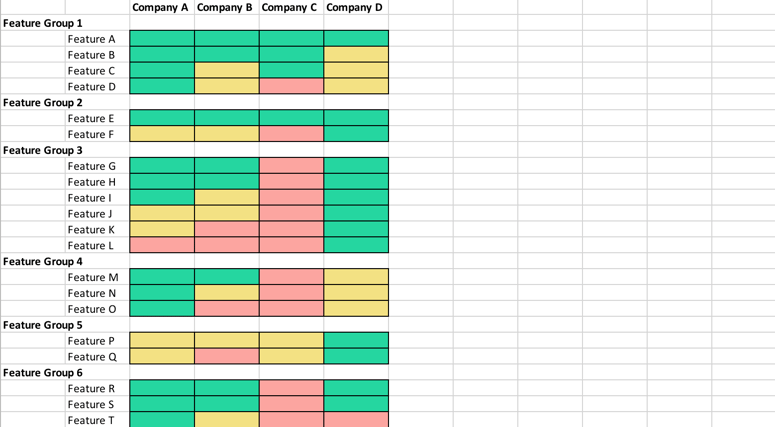

Let’s say, for example, that your primary goal is to improve positioning against four of your closest direct competitors. Accordingly, much of the data you’ve collected is related to these competitors’ products. Given your goal and the intel at your disposal, the most sensible variables to select for your analysis are features. The most sensible framework for your competitive analysis, in other words, is a feature comparison matrix:

As you can see, a matrix like this one makes it easier to organize, connect, and interpret your competitive datapoints (which, in this case, are product features). From here, you can—with relative ease—draw conclusions like this: “Compared to Competitor A and Competitor B, we deliver much more value from Feature Group 3. Let’s use that to our advantage whenever we need to position our product against either of theirs.”

Other applications of this competitive analysis framework include:

- Pricing. You’ve collected datapoints regarding your competitors’ pricing models. In what ways are these models (dis)similar to yours? From the POV of a prospect, in which respects is your pricing model superior to those of your competitors?

- Win/loss analysis. You’ve collected datapoints regarding your success (or lack thereof) when going head-to-head with specific competitors. Against which competitors are you most and least successful?

- Competitive landscape analysis. You’ve collected datapoints regarding your competitors’ respective sizes, maturity levels, and target markets. Which competitors are established? Amongst these, with which do you compete directly? Which competitors are emerging? Amongst these, with which do you compete directly?

2. Groupings

As we alluded to earlier, the optimal framework for your competitive analysis is often determined, in part, by the types of intel you’ve collected. There are cases, however, where you need to consider not only types of intel, but also volume of intel.

Depending on your goals, you may find yourself with an extraordinary number of competitive datapoints. As an example, let’s say you’re trying to develop a differentiated content marketing strategy—that is, you’re trying to create content that delivers value to your prospects in ways that your competitors’ content does not. Accordingly, your data set consists of thousands of blog posts, whitepapers, ebooks, case studies, and videos.

If you were to try to organize these datapoints with a framework along the lines of our feature comparison matrix, not only would you waste your time—you’d end up in place that’s no less overwhelming than where you started. In this case—and in others that involve similarly large quantities of intel—you’d be much better off using a grouping framework.

A grouping framework is a structure that allows you to categorize competitive datapoints according to high-level characteristics. As was the case with our previous framework, your goals will help you nail down the specifics (i.e., the characteristics you focus on).

To clarify, let’s continue with our content marketing example. Because your primary goal is to develop a differentiated strategy, you might decide to categorize your intel—your competitors’ blog posts, case studies, etc.—according to topic. This way, you’ll be able to determine which topics have been discussed ad nauseam, which topics have been neglected, and so on.

As this example illustrates, granularity is not required for a competitive analysis framework to be effective. Our hypothetical content analysis was conducted at a high level, but you were still able to organize your intel, extract meaning from it, and establish action items accordingly.

3. Hints of the future

In a sense, using a grouping framework is akin to zooming out—adopting a bird’s-eye view of the intel you’ve gathered and, from there, drawing high-level conclusions. Again, this is useful when your volume of data is so great that any other approach would be inefficient.

At the other end of the spectrum are those instances when you want to zoom in—when your data set is relatively small and consists of seemingly minute pieces of competitive intel. In our content marketing scenario, we were unconcerned with the details of individual blog posts. The opposite is true with a hints of the future framework: Each datapoint is subject to scrutiny.

You may wonder why someone would approach competitive analysis in this fashion. The short answer? Because a single piece of intel can indicate a major strategic change—one by which you and your stakeholders do not want to be blindsided.

Examples are useful here. Let’s say your company is in the auto insurance industry and one of your competitors has the following copy on their website: “If you’re under 25 and you haven’t been in an accident, you qualify for a discount!” One day, you notice a change: “If you’re under 30 and you haven’t been in an accident, you qualify for a discount!” It’s a small difference, but it could signify a big push to get a higher number of young customers in the door.

Or maybe your company is in the email marketing software industry and one of your emerging competitors—a startup—updates their careers page with a Sales Development Manager position. This is just one datapoint, but it indicates that your competitor is preparing to build out their sales development function—which means their growth rate is about to accelerate.

We could walk through ten more examples, but you get the idea: Competitive analysis isn’t strictly a matter of huge data sets and complex frameworks. Sometimes, it’s a matter of capturing the right intel in the right moment and having the wherewithal to see what’s coming down the pike.

Effective competitive analysis takes time—a lot of it

No matter which competitive analysis framework you use, turning intel into insight is a time-consuming process. Hurried attempts will yield unreliable results.

As such, it’s imperative that you reduce the amount of time spent gathering, filtering, and organizing intel. The more time you spend on these tasks, the less time you can dedicate to analysis—and the less confident you can feel about the insights you deliver to stakeholders.

Crayon can help. By continuously capturing and prioritizing data across your competitive landscape, we can help you give competitive analysis the attention it requires.

Related Blog Posts

Popular Posts

-

How to Create a Competitive Matrix (Step-by-Step Guide With Examples + Free Templates)

How to Create a Competitive Matrix (Step-by-Step Guide With Examples + Free Templates)

-

Sales Battlecards 101: How to Help Your Sellers Leave the Competition In the Dust

Sales Battlecards 101: How to Help Your Sellers Leave the Competition In the Dust

-

The 8 Free Market Research Tools and Resources You Need to Know

The 8 Free Market Research Tools and Resources You Need to Know

-

6 Competitive Advantage Examples From the Real World

6 Competitive Advantage Examples From the Real World

-

How to Measure Product Launch Success: 12 KPIs You Should Be Tracking

How to Measure Product Launch Success: 12 KPIs You Should Be Tracking